Last updated on

During the holidays in the United States, several posts circulated regarding purported leaks of Google ranking-related data. Initially, these posts centered on “confirming” beliefs long held by Rand Fishkin, but scant attention was paid to the context of the information and its true implications.

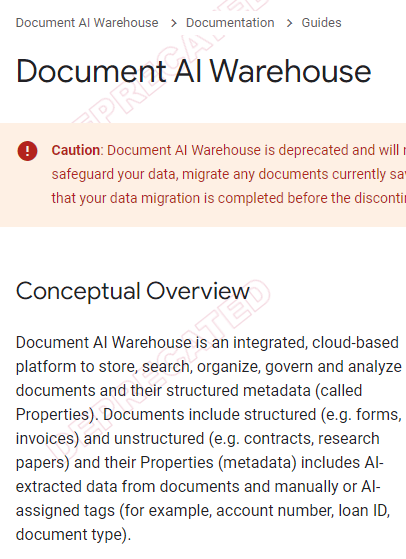

The leaked document is connected to a public Google Cloud platform known as Document AI Warehouse, designed for analyzing, organizing, searching, and storing data. This platform is detailed in public documentation titled “Document AI Warehouse Overview.” A Facebook post suggests that the “leaked” data is an “internal version” of the publicly accessible Document AI Warehouse documentation. This provides the context for the data in question.

@DavidGQuaid tweeted:

“It appears to be an external-facing API designed for constructing a document warehouse, as the name implies. This undermines the notion that the ‘leaked’ data pertains to internal Google Search information. Currently, the ‘leaked data’ bears resemblance to the content publicly available on the Document AI Warehouse page.”

The original post on SparkToro doesn’t assert that the data stems from Google Search; instead, it mentions that the individual who sent the data to Rand Fishkin made that assertion.

One notable aspect of Rand Fishkin’s style is his meticulous precision in writing, particularly regarding disclaimers. Rand precisely highlights that it’s the sender of the data who asserts that it originates from Google Search. There’s no substantiation provided, just a claim.

In his words:

“I received an email from a person claiming to have access to a massive leak of API documentation from inside Google’s Search division.”

Fishkin himself doesn’t confirm that the data was validated by former Google employees as originating from Google Search. He clarifies that the individual who emailed the data made that assertion.

“The email further claimed that these leaked documents were confirmed as authentic by ex-Google employees, and that those ex-employees and others had shared additional, private information about Google’s search operations.”

Fishkin elaborates on a subsequent video meeting where the leaker disclosed that their interaction with ex-Googlers occurred at a search industry event. Yet again, it’s necessary to rely on the leaker’s account regarding the ex-Googlers and the nature of their comments, assuming they were based on careful scrutiny of the data rather than casual remarks.

Fishkin mentions reaching out to three ex-Googlers regarding the matter. Interestingly, these individuals didn’t explicitly affirm that the data belonged to Google Search. Their confirmation was limited to the observation that the data resembled internal Google information, not necessarily originating from Google Search.

Here’s what Fishkin relayed from his conversations with the ex-Googlers:

“I didn’t have access to this code when I worked there. But this certainly looks legit.”

“It has all the hallmarks of an internal Google API.”

“It’s a Java-based API. And someone spent a lot of time adhering to Google’s own internal standards for documentation and naming.”

“I’d need more time to be sure, but this matches internal documentation I’m familiar with.”

“Nothing I saw in a brief review suggests this is anything but legit.”

Distinguishing between something originating from Google Search and something merely originating from Google is crucial.

Maintaining a receptive attitude towards the data is crucial due to the considerable amount of unverified information associated with it. For instance, the origin of this data as an internal Search Team document remains uncertain. Consequently, it’s prudent to refrain from extracting actionable SEO guidance from this dataset.

Furthermore, analyzing the data solely to validate preconceived notions is ill-advised as it can lead to Confirmation Bias.

Confirmation Bias, as defined, refers to the inclination to seek, interpret, favor, and recall information in a manner that aligns with one’s existing beliefs or principles.

Confirmation Bias can indeed lead individuals to reject facts that are empirically true. Take, for instance, the longstanding notion of the “Sandbox” theory, suggesting that Google automatically delays the ranking of new sites. Despite numerous reports of new sites and pages swiftly attaining top rankings on Google, entrenched believers in the Sandbox theory may dismiss such contrary evidence.

Brenda Malone, a Freelance Senior SEO Technical Strategist and Web Developer, shared her firsthand experience debunking the Sandbox theory: “I personally know, from actual experience, that the Sandbox theory is wrong. I just indexed in two days a personal blog with two posts. There is no way a little two post site should have been indexed according to the Sandbox theory.”

This example underscores the importance of avoiding Confirmation Bias when examining data, especially if it originates from Google Search. Instead of seeking validation for entrenched beliefs, it’s essential to approach the data objectively and without preconceived notions.

Consider these five points regarding the leaked data:

Ryan Jones, a seasoned figure in both SEO and computer science, offered insightful reflections on the purported data leak:

In a tweet, Ryan stated:

“We lack clarity on whether this data serves production or testing purposes. My speculation leans towards its predominant use in testing potential alterations.

Moreover, the data’s utilization across various web segments or other verticals remains ambiguous. Certain elements might exclusively cater to platforms like Google Home or News.

The distinction between inputs for machine learning algorithms and those used for training remains elusive. My presumption is that clicks do not directly influence inputs but rather aid in training models to predict clickability, excluding trending boosts.

Furthermore, I suspect that some data fields solely pertain to training datasets and may not encompass all websites.

Am I insinuating that Google provided truthful information? Not necessarily. However, let’s objectively scrutinize this leak without predisposed biases.”

David G. Quaid shared his perspective on Twitter:

“We’re also uncertain whether this data pertains to Google Search or Google Cloud document retrieval.

APIs appear selective, which deviates from my expectations of algorithmic operation. What if an engineer opts to bypass these quality checks? This resembles a scenario where one aims to develop a content warehouse application for an enterprise knowledge base.”

Currently, concrete evidence confirming that the “leaked” data originates from Google Search is lacking. The purpose behind the data remains shrouded in ambiguity, with indications suggesting it might merely serve as “an external facing API for building a document warehouse,” as implied by its name. Notably, there seems to be no direct correlation between this data and how websites are ranked in Google Search.

While it’s premature to definitively assert that this data didn’t stem from Google Search, the accumulating evidence points in that direction.

Original news from SearchEngineJournal